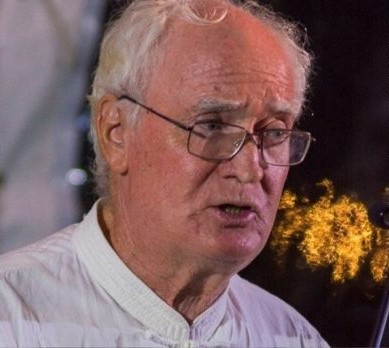

Ahead of appearing in Issue 43 of The Blue Nib, Australian poet, Peter Boyle speaks to Denise O’Hagan about his early influences, the poets who have inspired him, the intimacy of translation and why it is important to ‘let go of the hunger for fame’.

Peter Boyle is a Sydney-based poet and translator of poetry. He has eight books of poetry published and eight books as a translator. Recent books include the prize-winning Ghostspeaking and Apocrypha. His latest book, Enfolded in the Wings of a Great Darkness, won the Kenneth Slessor Award and was shortlisted for the Queensland Premier’s Award. His translations include Anima and Indole/Of Such A Nature by José Kozer, The Trees by Eugenio Montejo and Three Poets: Olga Orozco, Marosa Di Giorgio and Jorge Palma. In 2013 he was awarded the New South Wales Premier’s Award for Literary Translation.

Denise: Good morning, Peter, and I appreciate your making time for this conversation. As a translator from French and Spanish, as well as a poet, could you tell us how working between languages has affected your poetry?

Peter: First, Denise, thank you for inviting me to do this interview. From the very beginning, back in high school, my imagination was captured by poetry in other languages – poets like Lorca, Baudelaire, Rimbaud and Villon, as well as Sophocles, Virgil and Catullus. I was discovering those poets at the same time as Hopkins, Eliot, Pound and Dylan Thomas. Some of my earliest efforts in poetry consisted of making my own translations, I mean poems of my own devising, of Rimbaud’s ‘Le Bateau ivre’, Villon’s ‘Testament’ and the great poem ‘Polla ta deina’ from Antigone. I studied French, Latin and Greek in high school. I was fortunate to go to a very good college run by the Jesuits. Working between languages and, you could also say, between different poetic cultures widened my sense of what you can do in poetry. It fed my desire to push poetry toward its limits. I think the wideness, the expansion of poetry, is open to everyone, and you don’t have to write poetry in any one given way. Also, when you translate a new poet, like Cuban José Kozer, Venezuelan Eugenio Montejo or a French poet like Pierre Reverdy, Max Jacob or René Char, you have to listen closely to the sound and rhythm, the inner structure of the poem, the way it curves and shifts and does a great journey, often over no more than twenty or so lines. It helps you sense a poem as a musical structure.

Denise: I’m tempted to say that this could be a description of your own latest collection too – Enfolded in the Wings of a Great Darkness – curving and shifting and doing a great journey. Which leads me to ask how your own poetic journey started, and whether there was a particular prompt or set of circumstances?

Peter: I began writing poetry when I was fourteen or fifteen. I wrote a few poems that were published in the school magazine. At University I was very focused on my studies in Philosophy, English and German and wrote very little poetry, but still there were a few publications. In my twenties and early thirties, I spent a lot of time trying to write a novel. Around 1980, living in Madrid for six months, I worked on very loose translations of a few of Lorca’s poems. It helped free me up from the autobiographic or social-realism constraints of much of what happens in the English language tradition. For so long I couldn’t find a way to write the poetry I wanted. The models I was seeing about me in Australia and the United States at that time – people like Ashbery and O’Hara or Gary Snyder or Ginsberg – didn’t speak to me the way poets like Rilke, Lorca or George Seferis did, but you can’t just write like the greats of the early twentieth century either. Finding my own way into poetry was a terribly slow process. After I began writing poetry, I never really stopped, but poems that worked only came with any kind of fluency when I was about thirty-seven, after I was married with children and had completely separated the question of how to make a living from the question of what kind of a writer I wanted to be. I found a congenial, rewarding job as a teacher in adult education and looked on any poems I might write as a bonus to life.

My first book came out in my early forties. The realisation that I could do in poetry everything I had wanted to do in a novel was an important turning point. I remember reading Jules Supervielle when I was about thirty-two and thinking how everything Proust might do in a hundred pages Supervielle could accomplish in a thirty-line poem. I’ve also always been interested in prose poetry and the cross-over between genres. While still at University, in 1972, I had a piece, ‘From a window in Mosman’, published in Tabloid Story, and the story or sketch starts as prose and finishes with verse-form poetry.

Denise: This readiness to experiment with genres is evident also in the variety of the types of poetry you write. Could you tell us something about them, and what draws you to their different forms?

Peter: Apart from stand-alone poems, like the ones published in The Blue Nib, there are my heteronymous books – Ghostspeaking and Apocrypha. Heteronymous poetry has its origins with the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa who wrote all his poems through the medium of different imaginary poets, like the visionary mystic bucolic poet Alberto Caeiro or the Whitman-Futurist-inspired, overtly homosexual Àlvaro de Campos. It’s a way of opening poetry up to the possibilities of fiction and experimenting with different styles and voices. In Latin America, several poets write heteronymous poetry. Argentine Juan Gelman’s Los poemas de Sidney West are supposed translations of an imaginary US poet, Sidney West. I think it’s Gelman’s best book. Something very liberating happens when we step outside ourselves.

In Apocrypha I gather texts, prose and poetry, from imaginary poets and philosophers from the ancient world, supposedly translated by an invented character William O’Shaunessy, whose life in many ways resembles my own before I was married, very lonely and not heading in a good direction. In Ghostspeaking I invented thirteen poets and writers from Latin America, France and Québec whose poems I translate. I also supply biographies, interviews and letters from them. Their styles, subject matter and life stories are all very different. Paradoxically, I think, in some ways there is more of myself in Ghostspeaking than in any other of my books.

Denise: What a fascinating and unusual process of synthesis, an imaginative bringing together of created identities! Do you enjoy the same freedom in your current collaborative work with writers?

Peter: I have written several books of collaborative poems with MTC Cronin – one of these was published by Shearsman in the UK in 2009, How Does a Man Who is Dead Reinvent his Body?: The Belated Love Poems of Thean Morris Caelli. Margie and I write back and forth between each other, with no fixed rules – I am terrible at sticking to any rules – and poems emerge. We share the editing process as well. Patterns start to emerge and we find we are shaping a book. It’s great fun. One of my favourite poems from How Does a Man Who is Dead Reinvent his Body? is the long poem sequence ‘To Remain’ which consists of the alternating voices of a Japanese woman, a visual artist, and the ghost of a Chinese poet, the man who was her lover. Margie wrote the man and I wrote the woman who never gets to see the ghost, who is unaware of his existence, but always longs to see him.

There is something very liberating about writing collaboratively. Margie and I write of our collaborations as an experiment in ‘surrendering a certain level of control and letting the poem emerge from a combined effort, the poem less as one’s own story than something other than oneself, possessing an independent beauty or trace of life’s varied troubles.’ A new work of ours, Who Was by Alex Quel, is about to come out with Puncher & Wattmann. To me it feels good to get away from the assumption that every poem is some kind of autobiography, as if everyone has to be stuck to endlessly telling their own story. There are so many other things to do in poetry.

Denise: Tell me more about this, and the current trend towards ‘confessional’ poetry. Is it, do you think, a natural consequence of the greater number of people turning to poetry, and when does exploring ‘our own story’ through poetry cease to be self-indulgent, and become something of universal and timeless significance?

Peter: I wouldn’t want to dismiss anyone’s efforts to tell their own story as ‘self-indulgent’. People have every right to explore their own story, in prose or in poetry. Of course, not all efforts will be equally engrossing for others. Moving, profound, original poetry is difficult to make and often poems don’t quite work for all sorts of reasons. Likewise, I don’t think we can say with any great confidence, when we look at poems written over the last twenty or thirty years, which ones will last. Will James Wright’s or Frank O’Hara’s poetry still speak to people in a hundred years? Will they survive only on specialist University courses on late twentieth-century American poetry, like the many Elizabethan poets remembered now at most for single poems in anthologies? To set out consciously to write poems ‘of universal and timeless significance’ sounds like the worst possible strategy. I am sure it is not what François Villon, Geoffrey Chaucer or William Blake thought they were doing. Their poetry survives because of its energy and its deep humanity, because of the intense way they engaged with the world around them.

In a way ‘confessional’ poetry has long been a major trend in English-language poetry, in the sense that detail-rich poetry that references parts of the poet’s life has a long tradition going back at least to Wordsworth and Coleridge. Yeats’ ‘Wild Swans at Coole’ could also be read in that way. Poets like Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath, James Wright, Philip Levine, Frank O’Hara, Sharon Olds, Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder write extremely different poetry from each other, yet all of them write mostly out of their own lives, sharing specific details, whether it’s childhood trauma, the town they grew up in, or something as simple as O’Hara sharing a coke with the one he loves. I think poetry is individual not universal – it arises from intense perceptions of the particular. One problem with certain types of ‘confessional’ poetry is that they can have an unconscious universalising structure in them, which happens when someone sees their lives through the lens of pre-made boxes. Poetry, to me, works best when it channels the particular, when it lets in all the richness and ambiguity of an individual life. It’s also to do with the language. Poetry requires that something interesting, fresh, unexpected, happen in the language. If we are operating out of an overly self-conscious, socially constructed, category-dominated mind, some dynamic explosion in the language is much less likely to happen. I also suspect that, if you want to tell your life story, to get it out there so others can read it, a prose memoir or autobiographic novel is, for most people, a better way to do it. It lets the reader see the wider picture, the narrative sweep. I have met people who think poetry is so much easier to write than prose, but I think that’s a poor reason for writing your memoirs in poetry. A good poem is a very difficult thing to create.

As for the rise of ‘confessional’ poetry in the US, and in Australia as well, in the late 1960s, 70s and onwards, it had much to do with the larger number of people going on to Universities at the same time as massive social changes were taking place. So you had someone who was often the first generation of their family to go to University, and it was very natural for many of them to write poetry about their own lives: as working class people, as women, migrants and children of migrants, African Americans, gays, indigenous or First Nation men and women, for example. It’s not surprising that many turned to ‘confessional’ poetry, just as many wrote novels, autobiographies and short stories out of the details of what they had experienced. A lot of great literature has been written, and is still being written, in that way.

Denise: Thank you for your thoughts on this, very important for poets in this genre. You mention many writers who have touched you, whose influence you have embraced. Which other authors, including poets, are your main inspirations in writing, and have they changed over time?

Peter: Yes, the authors who inspire me have changed a lot over time, or – more exactly – I keep finding new ones. Proust, Camus, Dostoyevski and Patrick White are long-term favourites. Favourite poets include Lorca, Vallejo, Neruda, Rilke, Celan, Ritsos, Wallace Stevens, René Char and Henri Michaux, as well as Sylvia Plath, James Wright, Galway Kinnell, Charles Simic, and Elizabeth Bishop. There are many many others and I keep discovering new poets. I recently read the New Collected Poems of Eavan Boland and thought they were amazing. In some way they appealed to me even more than Seamus Heaney. I haven’t mentioned Edmond Jabès, whose brilliant trans-genre work The Book of Questions was an important inspiration for my own heteronymous collection of imaginary ancient poets and writers, Apocrypha. Others who have inspired me include Italo Calvino, Antonio Machado and the Mexican poet Gerardo Deniz. It’s an always open list of new discoveries, but I also do a lot of rereading.

Denise: I am interested in this question of what it is in other people’s poetry that attracts you, and the qualities to which you find yourself drawn. What was it, for instance, in the poems of the late Eavan Boland which particularly appealed to you?

Peter: There is this incredible growth in Boland’s poetry from the first books with their myths and Irish content and strong sense of Yeats to the far more intense, visceral poems of In Their Own Image, and then, to me, the masterpieces start from Night Feed onward. There’s a delicacy, a respect for life, an ability to let the lines and phrases point beyond themselves, and all the time to hold fast to life’s complexities. I love the way in a poem like ‘Domestic interior’ the woman in a Van Eyck painting, ‘as round as her new ring’, is described as ‘interred in joy’. Simple things that Boland does with such magnificence: it’s a very subtle poetry and feels entirely her own. Small things are made to carry the give and take of our often confused emotions. There’s an immense power in understatement and Eavan Boland is a master of it. You get phrases like ‘hardened by/ the need to be ordinary’ in ‘Self-portrait on a summer evening’ or ‘a noiseless coming head on/ of red roofs’ in ‘After a childhood away from Ireland’. Equally I love the way, in a poem like ‘The Latin lesson’, she can start with the most prosaic, mundane details, set down simply, no frills, and then leap to an image of ‘these/ shadows in their shadow-bodies/ chittering and mobbing/ on the far// shore, signalling their hunger for/ the small usefulness of a life…’. It’s quite an extraordinary, wonderfully developed image, but the poem doesn’t stop there. It comes back, appropriately, interestingly, to the consciousness of a teenage girl who gets, and doesn’t get, death.

And there’s another dimension to Boland’s work. She writes often about her own life, the life of a woman of her time, of domesticity. At other times she writes of Ireland’s past, particularly the horrific years of famine. But always she looks deeper. She works so that the poetry goes beyond what we know or think we know already. It’s never just an autobiographic fragment or a history lesson. Poems like ‘Formal feeling’ or ‘Quarantine’ have a many-sided depth to them that comes from, in some way, surrendering to the strange art form that poetry is.

Denise: In this analysis of Boland’s work, you offer us something very close to a definition of poetry, as well as suggesting what poetry isn’t. Among the poets whose work you have translated, who have most inspired you?

Peter: Translating a poem, and especially translating a whole book of poems by one author, is a very intimate experience of a particular voice and sensitivity, a specific dynamic of how that poet imagines poetry. In the late 1990s, at the request of the Peruvian consul in Sydney, I produced a bilingual selected poems of César Vallejo, and Vallejo’s sense of balance, of radical shifts in perspective from the mundane to the universal, from bleakness to hope, alongside a kind of radical innocence, still helps shape poems I write today.

Eugenio Montejo, whom I met in Medellín in 1997, was another important influence. His sparse simplicity and ability to say a lot with the minimum of words have been a great influence. Again, Montejo possessed an extraordinary aura of human goodness. It’s an honour to translate poets like that, poets who write extraordinary poetry. I especially like to translate those who haven’t yet been translated much and who offer something, an approach or a path forward, I can intuit but haven’t yet explored in my own work.

José Kozer is another maestro of poetry whose approach is totally different from Montejo’s. Kozer’s poetry is baroque, ornate, detailed and multi-layered, but it also slips into these oneiric moments of pure vision. And there’s Marosa Di Giorgio who pushes prose poetry to the edges of a kind of surreal novel, very feminist, very political but in a hidden way, and Olga Orozco, an Italian-Irish-Argentine bruja who brings the supernatural into her poems. Their voices, their aesthetics, are all different, but I have learnt from all of them.

Another poet I’ve translated a body of poems by is René Char – this was back in the late 90s and early this century when many of his poems were not readily available in translation. I was especially inspired by Char’s prose poems and aphorisms where the poetry is not tied to personal storytelling or portraits out of life. I love Char’s capacity to let the poem break free, to allow instinctive images to guide it. A good example of what I mean is the poem ‘Jacquemard and Julia’. I will give you my translation that was originally published in the US in Verse magazine:

Once upon a time, at the hour when the earth’s roads unanimously sank below the horizon, the grass tenderly stretched out its shoots and kindled its first rays. Knights of that era were born in the gaze of their love and the castles of their beloveds had as many windows as the abyss carries mild storms.

Once upon a time the grass knew a thousand proverbs that in no way contradicted each other. It was a kindly providence for faces bathed in tears. It enchanted animals and offered delusions a safe haven. Its domain was as vast as the sky which has conquered the fear of time and softened pain.

Once upon a time the grass was kind to madmen and hostile to the hangman. It cast aside its widow’s weeds at the threshold of forever. The games it invented had wings in their smile (exonerated fleeting games). In those days it wasn’t hard for those who lost their way, and wished to do so, to lose it forever.

Once upon a time the grass had established that night is of less importance than its power, that the sources of rivers don’t wantonly complicate their courses, that the grain that kneels down is already half way in the bird’s beak. In those days earth and sky hated each other yet lived together.

Unquenchable dryness flows out. Man is a stranger to the dawn. In the pursuit of a life that can’t yet be imagined, there are wishes that groan, murmurs that try to face themselves, and safe sheltered children who discover.

I think in Char there is an immense trust in the ability of the imagination, as channelled through poetry’s sensitivity to sound and rhythm, to take us somewhere new. I love what he does with the prose poem, in my own definition of the form: a piece of writing that’s so obviously a poem it doesn’t need line-breaks to prove it.

Denise: I must remember that definition the next time someone asks me, ‘But what exactly is a prose poem?’ You have described poetry as giving space to the unconscious side of our life, our ‘accidental real life’, rather than just our opinion-oriented, public persona. Can you tell us a little more about this?

Peter: If someone asks you, ‘What do you think about Australia’s refugee policy?’ or ‘What do you think about coal mining in Australia?’ we give our opinions, they should do this and this because of this and this and what they are doing now is appalling because of . . . Likewise, if I’m getting to know someone and they ask me about my childhood I can say, well when I was eleven we moved from here to here and it was a big up-wrenching because of such and such. But all this is a very very long way from poetry, or at least from the poetry that most appeals to me. Unless you are viscerally involved and it’s your life that’s on the line, it’s mostly ourselves from the neck up talking, mostly in set phrases. It’s a kind of paraphrase of inner thoughts and not likely, for the most part, to engender poetry. Reason dominates and, even when we’re intense in our beliefs, the phrases tend to be set phrases, ready-made clumps of words we reassemble. That kind of reasoned discourse is immensely important of course, as is the sharing of childhood experiences and the broad, socially communicable, dimension of our life. But I think we all sense that that isn’t all there is to ourselves.

Inwardness, what dreams throw up, and above all the imagination, have the capacity to bring the whole being into play, so the heart, the whole body and something different in the voice enter into the words. I think there’s a human intuition that there’s another speech, which could be like magic spells or like the profound echo of song or a line out of Shakespeare or Dante. I think, for those of us who love poetry, we’ve known the shiver of emotion as if a hand has just brushed us with a piercing tenderness. The deep things of life: absolute love, loss, death, the sense of abandonment, joy in being fully in the moment, the surprise of unexpected beauty, but also grief and deep, personally felt experiences of injustice: all cry out for a different kind of speech. Eugenio Montejo wrote, ‘A poem is a prayer spoken to a God who only exists while the prayer lasts.’ Art, music, poetry can all open up that other side of ourselves – through them we can reach deeper into the experience and so help ourselves, and hopefully others, to see those experiences on a different level, liberated from shut-down patterns. And the imagination means that we can experience these things not just through the random details of our own lives but through insights into others’ lives or the life of a plant or animal or through a work of music or art. In a long poem about his grandfather’s death, a long ritual-like poem in which his grandfather’s death merges with the death of his namesake King David, José Kozer writes, ‘I am free. In my imagination I am free.’

Poetry, like meditation, is a passage into a different dimension that is also right here among us. It’s hard to explain this well. It isn’t a matter of some sloppy Shelleyan or orphic view of poetry, but I don’t think poetry is just a matter of craft or some bundle of techniques laid on over our everyday opinions or personal life stories, however intense they may be. In the poetry that speaks to me, some kind of transformation happens. It feels like the poem is coming from somewhere other than the opinion-based, ego-centred mind. Rilke said that poets have to do ‘heart work’. He never talked much about craft.

Denise: Actually, you’ve explained beautifully the transcendent-yet-grounded aspect to poetry, the side that gives voice to the part of us which lives beyond the clamouring of the intellect. Bearing this in mind, how do you think people should be introduced to the study of poetry, and do you think it can be taught?

Peter: I think, for most people, poetry is killed in high school. No sooner are they given a poem than they are expected to talk about it, analyse it, write about it. Imagine if every time a child was shown a painting or listened to a piece of music they were expected to write an essay on it or fill in a quiz about its meaning and techniques. Poems are treated as if they were strange texts that have to be decoded, as if the moment you see line-breaks we automatically enter some mysterious realm, which is nonsense. Poems can be good or bad, banal or weird, electrifying unexpected visions or sloppy servings of sentimentality. They can be powerful, humorous crystallisations of some common experiences, perfectly accessible to anyone, or they can be vivid oneiric conjurations whose meaning is deliberately left open. Poems will speak in different ways to different people at different times for all sorts of reasons. The important thing should be to encourage young people to read widely, to try many different poets and poems, to see if anything there speaks to them. If it doesn’t that’s fine. Maybe they will discover poetry when they are twenty-five or fifty. The important thing is not to feel spooked by poetry in advance, but to remain open to it.

In high school I was lucky to have good teachers of poetry who read it aloud well. Too many teachers don’t get poetry and, perhaps because of this, reduce it to its sociological content. I think that happens a lot, both at schools and universities. Mediocre poetry, then, can easily be elevated well beyond its merits simply because of the subject matter. Or, perhaps more to the point, having no real sense for poetry, people lose any instinct for making artistic distinctions, as if a poem was the same as its précis or the essay you could write about it. It’s similar to a trend in the visual arts where the artist statement seems more important than the actual work of art. In both cases the real experience is lost. But it goes deeper than that: poetry, like art, offers a different way of knowing, not controlled by the set categories, the fixed boxes society uses to filter the world. It escapes control. It might lead people to think and feel differently, and perhaps that is why there has been a steady trend, conscious or unconscious, to reduce it to simple fixed messages, in effect to shut it down.

Denise: There is a strong sense of journey in your own ‘heart work’, and Enfolded in the Wings of a Great Darkness is rare in that it takes the form of a single extended poem. Is the conclusion of a poem known to you at the start, or something you work through in the writing?

Peter: A poem has to be a discovery. If I knew in advance where a poem was going and could paraphrase what it means and state my intention, why would I write the poem? What energy would there be to drive it? With Enfolded in the Wings of a Great Darkness I began with the very short poems that stand at the start and gradually it kept growing. About halfway through I realised what the last line should be but still didn’t know how I would get there. And for quite some time I had the final short poem almost right but couldn’t get the final line to be where I wanted it. I was staying briefly in Alice Springs with Debbie, my late partner, to whom the book is dedicated, and reading the final volume of a biography of Kafka and a French translation of the Midrash Rabba on Ruth and Esther, and finally that section of the poem came clear with the final line, the book’s title, as the close of the book. But further short poems were written after that and slotted at various points into the sequence. I wanted the book to feel like one singular out-flowing, though it was not composed precisely like that. It was more an organic growth. About half-way through writing Enfolded I reread Inger Christensen’s Alphabet and that also helped me shape the book. I don’t follow a formal structure like Christensen’s, but I learnt a lot from the way she uses a back and forth flow between life’s different dimensions and frequent tonal and structural changes to give her book-length poem coherence without monotony.

Getting back to your question, as I began the first short poems in Enfolded I was writing out of where I was at that moment, living with my partner who had an incurable form of cancer and, by then, had perhaps two or three years to live. I was writing that experience with no real knowledge of where the poem or the experience would take me. I might have given up writing but Deb, my partner, certainly wanted me to keep going. She read the poems as I wrote them and, despite the chemo and the spells in hospital, she was at the same time writing her own book on flying foxes and their carers, on living and caring for creatures and a planet on the edge of extinction. I finished Enfolded in time for Deb to read a published copy before she died, thanks to the generous work of the editor, Michael Brennan. I knew I didn’t want to write a chronicle of visits to doctors and hospital wards. It wasn’t my fight with cancer I was writing. It was about living in death’s shadow and trying to find a valid way to point towards whatever that might signify, to bear witness to whatever was terrible or beautiful in the day-to-day living of that reality.

Denise: Although we may shy away from it, the question you raise so eloquently in Enfolded is one we all must ultimately face, in our own way, and I thank you for sharing the background with us. Much has been written about the consoling aspects of poetry, yet the subjects delved into can be confronting as well as inspiring. When you have finished a poem, what impact can it have on you, as writer?

Peter: When I finish a poem, if I’m happy with it, it goes over to the reader and, in a sense, I withdraw from it; it’s no longer mine. Often, in the process of writing a poem I can feel that some blockage or grief or dark space in myself is being released. Poems can be much wiser than we are ourselves. Temporarily, while I’m writing it or just after I’ve finished, I can feel a kind of elation. I don’t write that many poems directly out of my life in the sense of autobiographic poems or poems about my childhood. There are a few. I contracted polio just before my third birthday and for a long time was unable to walk. I still have a paralysed right leg. There’s a very short poem I wrote that describes my first memory in life. After I wrote this poem, and whenever I read it in public, I feel very moved, both by the presence of my father in the poem and by the sense that in the midst of illness I am blessed. The poem is called ‘Paralysis’:

Laid out flat

in the back of the station wagon my father borrowed

I look up:

the leaves are immense,

green and golden with clear summer light

breaking through –

though I turn only my neck

I can see all of them

along this avenue that has no limits.

What does it matter

that I am only eyes

if I am to be carried

so lightly

under the trees of the world?

From beyond the numbness of my strange body

the wealth of the leaves

falls forever

into my small still watching.

Denise: Thank you for this moving glimpse into a part of your life, and into your ability to feel yourself blessed in being ‘only eyes’. You’re not the first artist to find in adversity a new perspective, energy even. Do you feel that challenge can be instrumental in helping us find our voices as poets?

Peter: Every experience, joyful or painful, boring or transfiguring, can help us grow and, in ways we don’t understand, lead us to find a voice as a poet. I’m not sure if I altogether like the expression ‘finding your own voice as a poet’. We can write different poems in very different styles responding to life’s changing circumstances, but I guess there is a sense in which poets transition from being somewhat imitative and unsure of both their style and what to write about. To me that was clear when reading Eavan Boland’s Collected Poems. I felt there was a deep transition between her first poems and what she was writing from about 1980 onwards. You could call that transition ‘finding a voice’. And often, by no means always, adversity is part of that transition. Everyone experiences suffering in one form or another. It can be an obvious, externally visible condition like poverty or being part of a group who suffer discrimination. Or it can be less visible, like loneliness, depression, self-loathing or other mental problems. I don’t believe there’s a hierarchy of suffering or that poems by those who have suffered a lot are necessarily any better than poems by those who have had a fortunate, mostly happy life. For every suicidal Sylvia Plath or Paul Celan there is someone with a fairly comfortable life like Rilke or Wallace Stevens.

Another way of looking at the role of suffering in poetry would be like this. If X had a more horrific life than Y, if their life went further into hell than Y, that tells me little about the value of X’s poetry. A prose collection of statements by X and by those who suffered the same kind of hell might well be far more moving and useful for society to hear. If X’s poetry went a long way into hell, exploring it, capturing what it felt like, going beyond the set narrative phrases society offers, that will be extraordinary poetry. If you read Raúl Zurita’s INRI, for example, you will see what I mean. It’s as if he is channelling the dead of Chile.

I’ve mentioned how in the poems that speak most to me there has to be a transformation, some explosion in the language and the imagination that takes me somewhere new. Merely having had a tough life or an appalling childhood doesn’t by itself create a poem. The ability to go deeper, to find ways to make that come alive for others, is something most writers and poets have to work towards. Also in poetry, just as in novels, there is room for imagination and empathy. A poet like Lorca or Vallejo can write about the suffering of others through a very deep, genuine power of empathy. Vallejo had a very tough life with poverty, extreme poverty, and exile. Lorca had his sufferings but most of his life was comfortable. Both of them wrote magnificent political poems – Vallejo’s Poemas humanos and Lorca’s Poeta en Nueva York. Lorca could see the racism and misery in America, intuited, personally understood from a relatively brief visit, ten months, and transformed it into poetry. Empathy, in a positive sense, is something very real that writers, especially poets, can use to write beyond themselves. It’s ludicrous and very damaging to literature to pretend we can only write about ourselves or the group we belong to. If we can only ever write about ourselves how could any work of literature contain more than one person? There would be no plays, no novels, no films, and human empathy, the capacity for empathy which helps us stop killing each other, would be drastically undermined. Poemas humanos, Vallejo’s provisional title for his late poems, poems unpublished in his lifetime, says it all. Vallejo was a cholo, an indigenous American of the Andes. He wrote in exile of those around him, the working-class poor of Paris, the drifters and itinerants. He didn’t say, ‘Oh my God, these people are French. If I write about them I’ll be ‘appropriating their suffering.’ He offers his poems to all of us as simply a ser humano, a brother to everyone.

Denise: On a different note, in the current climate of ecological crisis and political wrangling over funding to the arts, what role do you feel poetry does, or could, play in our society?

Peter: Poetry is a very democratic art form. Every year about a hundred new poetry books come out in Australia – that’s a thousand books in a decade, and I don’t think that figure would include all the self-published books or books by very small publishers. Of course, several people will have produced three or four books in ten years, but that still would suggest a figure of, say, 600 published and seriously regarded poets in Australia. And that’s not counting the many people who write poetry but have never had a book published. So, though people say no one reads poetry, a lot of people are writing it. How many Australian films have been produced in the last ten years? Films are enormously expensive. The average person can’t just decide to put a full-length film together but they can write poems. In terms of value for money, and giving a voice to everyone who feels they have something they want to say for whatever reason, whether that’s personal or because they are part of a group who are marginalised or because they hunger for something beautiful and unusual that hasn’t been expressed before, funding poetry makes a lot of sense. Poetry has a very real personal and social role to play. It’s inclusive and offers the individual an immense freedom to create.

As far as the ecological crisis goes, it is part of our consciousness. It infuses the world we live in, so the sense of living in dark times inevitably comes into the poetry any open, receptive poet writes. There is a strong eco-poetics movement in Australia and a journal like Plumwood Mountain features a lot of it. Many people write directly about environmental and social issues, and much very accomplished, very interesting poetry is written that way, but I think poetry can also operate more indirectly, in a subtler way. Personally, the poetry that speaks to me most can be about anything, or it might start with one thing and then slide into being about something else. I especially like poems that look for the spaces between things, sidestep and swerve, and end up taking me somewhere new.

Denise: That’s an excellent summing up of the quiet power of poetry in our society, and rather encouraging to our readers, too. Before we conclude, I have some general questions on aspects of writing which everyone always wants to know. All writers have their own ways of working. Can you describe your own approach to writing poetry, and whether you have a set routine, including editing?

Peter: For most of my productive writing life I worked full time as a teacher at Bankstown TAFE and was also very busy as a parent of two children. I did my writing late at night or in the middle of the night or sitting in the car while watching my son or daughter play soccer, in spare moments as they arose. I have always written by hand in notebooks that I keep, journals that are full of everything – trivia, casual observations, reflections on what I’m reading, but also poems or phrases that end up in poems. There was no set routine. Poems came or they didn’t, but I found that if I filled up the pages and kept scribbling away, poems did arise. Some come quite rapidly, virtually complete in twenty or forty minutes, others I need to go back and find where they might be leading after letting them rest for a day or two. I can’t make the poems come but I can try to trick them into emerging by various techniques I use: playing with words, writing in another language like French or Spanish – a couple of my poems were rough-drafted in Spanish first, then I did the English and expanded them. I also might sit myself down at a café and dedicate an hour to filling three or four pages with rapid writing.

Since retiring from TAFE in 2014 I have been trying to build a new routine to my writing, but from the end of that year till December 2018 I was very busy looking after my late wife. Since her death I am again trying to establish a routine. I would like to say I write every day, but I don’t. Some weeks are taken up with other tasks – editing my translations for publication or dealing with domestic or health matters. If I find myself constantly editing a poem it usually means that there was never sufficient psychic force behind it, so I drop it and do something different. For me, poems either arise fairly naturally or they don’t work at all. Very long poems or poem sequences are a different story. When I am caught up in such a process, the poems can come much more frequently, and I may do a lot of work editing them and deciding where to place them, how to arrange the whole sequence.

Denise: What type of poetry projects, for want of a better term, do you engage in?

Peter: I am very wary of the notion of a poetry project when it comes to myself. I don’t work well with constraints and am loath to try to write a body of poems on any pre-set subject or following one specific style. For me things have to happen organically, as I go along. Even with Ghostspeaking, which was the central part of my Doctorate in Creative Arts, I had already played around with it for some time, watched it grow and written up several parts of it before putting it forward as a project. For me poems have to erupt of their own accord. I can’t will them into being. So normally I avoid projects.

One exception was last year when I accepted a commission from the Art Gallery of New South Wales to write a poem on any artwork from their permanent collection. I knew 2019 would be a difficult year for me after my partner’s death and I thought it would be good to do something that would take me out of myself. I ended up writing not one poem but over a dozen, not only on works in the New South Wales Gallery but also on paintings in the White Rabbit Gallery and S.H. Erwin Gallery and from reproductions of art works online. For most of these I adopted a different approach to writing compared to my usual habits. I stood in front of the work, scribbling impressions rapidly, then sitting in the Gallery cafe I’d work over them, then return to the artwork to see if there was more I wanted to add. In the end I was quite happy with several of these poems, but if someone gave me a similar commission today, perhaps I’d be unable to write a single poem using those strategies.

Denise: It is becoming clear that you work in a fluid, responsive way, depending on the context, opening yourself up to the situation and resisting any formulaic approach. What have you in mind for your ekphrastic work, and may we look forward to reading some of it soon?

Peter: Several of these ekphrastic poems are going into the new book Notes Towards the Dreambook of Endings. It’s a collection of separate individual poems, but the last third consists of a poem sequence with the same title as the book. There are currently 36 sections in the sequence, many of them prose poems arising from dreams I’ve had, but interspersed with shorter verse-form poems. In the earlier two sections there are several of the ekphrastic poems as well as others addressed to Deb or, in general, dealing with my own grief and loss. One of these is entitled ‘The mind adrift: lying awake without you on the night of a heatwave’:

I am going across the mountains to find you.

It is midsummer and the mountains are full

of enormous moths. They have faces that resemble the moon.

They may well be a thousand small moons.

Glowing in the caves of the sky.

Beyond the mountains

In the small house where I find you

the sound of moths beating at the windows

is the light finger-tapping

of the immense irreplaceable.

In the middle of the insomniac night

pink cherry blossoms come and break open

in my silent room.

A fan whirring faintly

against the day’s lingering heat

gently sets them spinning

over the bed which is empty.

The Buddha statue is motionless as always

though I do not know what happens behind its eyes.

On a shelf three books rest.

The floor is bare wood, blemished with

black marks in its grain while shadows

lie under half-open doors.

All this small world that was our nightly cave –

in our separate realms, how far away are we both

from the birth of the universe?

Denise: Thank you for sharing this poignant poem – I think many will relate to this. Could you tell us a little about your other forthcoming books?

Peter: I’ve mentioned that my collaborative book with MTC Cronin, Who Was, is about to come out. The title can be read in several ways, possibly as an affirmation of existence or as elegiac for someone who has gone. The poem sequence that forms most of the book has fifty-five numbered sections, some only a few words, others as long as a page. When I was reading back over it for this interview, one section that leapt out at me was XXXIX. I have no idea which of us wrote this, or if it was started by one of us and finished by the other, though Margie says she can always identify who wrote which lines:

Here at the end of summer and winter

the light is so absolute

it is enough.

Margie Cronin and I have also almost finished a new manuscript of collaborative poems, Little Book of Dozens. Each section has a dozen poems. So you have ‘Little Book of Animals’, ‘Everyday Spells & Magic Reversals’, ‘The Trees’ and other sections, all consisting of twelve poems. Some of the poems are humorous and satirical, like those in the section ‘Starting Anti-School’; others are more serious, as in ‘Little Book of Conversations & Transformations’ where we approach themes of war, oppression and violence. In this book we decided to note after each poem which one of us wrote it or if it was written by the two of us. The whole book is collaborative in the sense of being a shared work. Being placed in the book, each poem is like a gift to the other, so the book celebrates the notion of poetry as a gift that goes out to whoever may read it, something that has left the ego-focused self behind.

Denise: We’ll be looking forward to the publication of both these collections. What books are you currently reading, poetry or otherwise?

Peter: Last week I reread The Book of Nightmares by Galway Kinnell and Elegy and The Widening Spell of the Leaves by Larry Levis. I first read both these books about twenty-seven years ago, so I was curious to see if I’d remain as enthusiastic about them now. I was again spellbound by how moving the poetry is and by the sheer energy of the writing. I’ve just finished The Fox Papers by Jennifer Maiden and Throat by Ellen Van Neerven, both very powerful, imaginative collections of poetry.

At the moment I am reading a book-length interview of José Kozer, José Kozer: tajante y definitivo by Gerardo Fernández Fe. Kozer’s life is a very interesting one. He turned eighty this year and in the interview looks back on a complex, sometimes very painful, life as someone who is Jewish and Cuban, has lived in the United States since the age of twenty, is not in any way right wing but detests dictatorships of any kind – and for that reason found it hard to publish anywhere in Latin America in the 1970s when, for writers and intellectuals, being pro-Castro was largely de rigueur. Kozer’s poetry is not political or about migrant or exile experience – so again, apart from not being in English, it doesn’t fit into Latino poetry inside the US.

Similar things happen everywhere in one way or another: narrow agendas are set and people get excluded, sometimes because of a simplistic political map of the world, or because of false dichotomies about style and content, or it may be because of an assumption that someone of a particular ethnic background or social group must spend their life writing only about what is called their ‘identity’. In Australian poetry, for example, the push has long been for poets to write about strictly Australian topics, about what being Australian means or what is specific to our landscape, our vernacular speech, our historical and social issues. University courses on Australian literature typically start with Henry Lawson, go on to Les Murray and Robert Gray who often have a rural emphasis in their writing, and then move on to Indigenous and migrant writing which is also largely about specifically Australian experiences. There’s a lot of fine writing and excellent poetry in this tradition but it leaves out those like Christopher Brennan and Francis Webb, or contemporaries like Philip Hammial and MTC Cronin, whose poetry is more universal, experimental, personal rather than narrowly and consciously ‘Australian’, whose work isn’t focused on identity. Equally it overlooks poets like Michelle Cahill or Prithvi Varatharagan whose poetry doesn’t fit the migrant-story genre.

For me, poetry has to be free, every poet has to be free. Kozer’s poetry has a definitive style. You can easily recognise one of his poems, but it can be about anything: his family, the complexities of everyday life, the approach of death. I’ve enjoyed reading his very frank account of his life. Biographies and autobiographies, and non-fiction in general, alongside poetry, are my favourite books to read, though I also read novels.

Denise: What an eclectic range of books! What advice would you offer to aspiring writers, especially during COVID-19 and its aftermath?

Peter: Read a lot and don’t worry if poems don’t seem to come. Be patient. Yes, it’s important to keep writing, but I think we need to keep our ego out of it. It’s all too easy to get upset, or start projecting ‘them’ and ‘us’ stories, if we can’t get published or our books or poems aren’t taken up by the media or the academy. Thousands, literally thousands of people write. What do we read from the late nineteenth century now? A tiny handful of poets out of the thousands who wrote back then. Look back over the complete list of twentieth-century Noble Prize winners for Literature, supposedly the crème-de-la-crème of world literature. Almost half of them are mediocrities few people read today. Most of the century’s great poets and novelists aren’t on that list. Remember writers like Cavafy and Kafka who were little read in their day. If your aim is to write something valid, powerful, profound, then patience, persistence and a certain degree of humility are necessary.

Denise: In a frequently marketing-driven world, where writers are encouraged to be active self-promoters of their work, how timely to be reminded of the role of humility! Which reminds me that any discussion of poetry and publishing today that doesn’t mention the all-pervasive reach of social media is perhaps incomplete. Most of us write largely if not entirely at the keyboard now, and rely heavily on social media for our work to reach an audience, including for this interview. So the final question I’ll put to you is: do you feel there is a dark side to this and, if so, how would you counsel poets both aspiring and establishing in the art of handling it?

Peter: This is a good question that has many sides to it. We are writing this interview in a Word document sent back and forth over emails, taking a few weeks to do it, and it will go up on a poetry website which makes it available to many people. We are both taking our time to do it and thinking over it slowly, carefully, respectfully, which seems to me very different from social media spaces like Twitter. There are good reasons why I write my poems – as opposed to articles, essays or most translations – by hand in a notebook. I can write rapidly, add alternatives, use arrows to suggest where a new image might go, and simultaneously see a range of options. I’m not in danger of over-correcting myself and having the first draft disappear. It’s much safer than relying on computers where, for all sorts of reasons, something may not save.

Also, when I type up a poem it marks for me the transition to a second stage of editing. It signifies I have a poem but it may not be in its best form yet, so I look at it afresh. The other advantage for poetry is that writing by hand is a very physical process that puts you in touch with your childhood self when you first learned to write. For me computers don’t replace handwriting – they replace typewriters.

But there is a deeper issue at stake here than the pros and cons of computer technology or social media. Every artist, a poet, a novelist, a visual artist, is to some extent torn between two tendencies. On the one hand, we want to see our work get out there – find publication, get reviews, gain an audience; we want recognition. But, on the other hand, we need an ego-less space of concentration and withdrawal in which we surrender to what this poem or artwork demands of us. And once that artwork or poem has left our hands, if we are to continue to write poems, we need the same ego-less receptivity to what the next poem is asking of us. If we spend our time promoting ourselves, we undermine our capacity to produce art. We can also get into a very bad headspace when we realise almost no one is reading us. Admittedly it’s very hard to keep writing poetry if almost no one reads your work, if – for example – you self-publish a book of your poems, and it goes unnoticed, has almost no readers. But that is precisely what happened to César Vallejo with Trilce that he published in 1922 in Lima – in his words the book went out into ‘the most absolute void’.

Returning to your question, we have to decide how we will draw the balance between the desire to promote our work and the need for inner focus. If your goal is simply fame, I would say ‘don’t bother writing poems.’ You can get more social media hits through cute photos of animals. Pop stars and actors, sports stars and celebrities, are the ones who are famous. A certain amount of self-promotion is good. Sending poems out to magazines is a good idea. Working to see if you can get a book published is sensible. Doing live readings is a good idea – not just to attract readers, but because you learn a lot about your own poems from reading them to others. It can help show you things that aren’t quite working. Maybe pasting links on your Facebook page to poems recently published is a good idea. It lets friends and family see it, but if it starts to feel uncomfortable, too up-yourself, there’s no compulsion to do it.

Particularly with poetry, part of its great strength as an art form is that it isn’t a career. It doesn’t pay well and never has. So there’s no compulsion to research what the latest trend is and write about that. There’s no compulsion to push your products. It isn’t, or shouldn’t be, a market-driven commodity. The merit of poetry is that it can step aside. It can escape late, twenty-first century, global capitalism, just as it escaped the totalitarian regimes of Stalin or the Greek junta or Pinochet. It can go under the radar. And so often the poets whose work survives are not those who won prizes or were greatly esteemed at the time. If we look back at the history of poetry we can see that. We keep reading Emily Dickinson and Hopkins, and very few of the ‘big names’ of Anglo-American poetry as perceived by the establishment of their times.

I think if you want to be a really good poet you have to let go of the hunger for fame. Some degree of recognition, a very small or slightly larger readership, will happen or it won’t happen. It may happen only after you’ve passed away. It may well happen briefly in a short fizzle that disappears. If you are looking for fame and recognition through your poetry – in this I’m talking to myself as much as to anyone else – you will always end up disappointed. It will never be enough. Your task is to remain unfazed. At least you will know in yourself that you have written the best that was in you.

Denise: We shall have to end here, but not before I thank you for giving of your time so generously and thoughtfully, for opening your own heart to us, and for your profound reflections not only on your poetic tastes and practices but also on the nature of poetry itself and how its ‘different kind of speech’ offers a response to the deeper things in life.